That's not a knife!

Some (uncritical) midlife thoughts on rewatching Crocodile Dundee

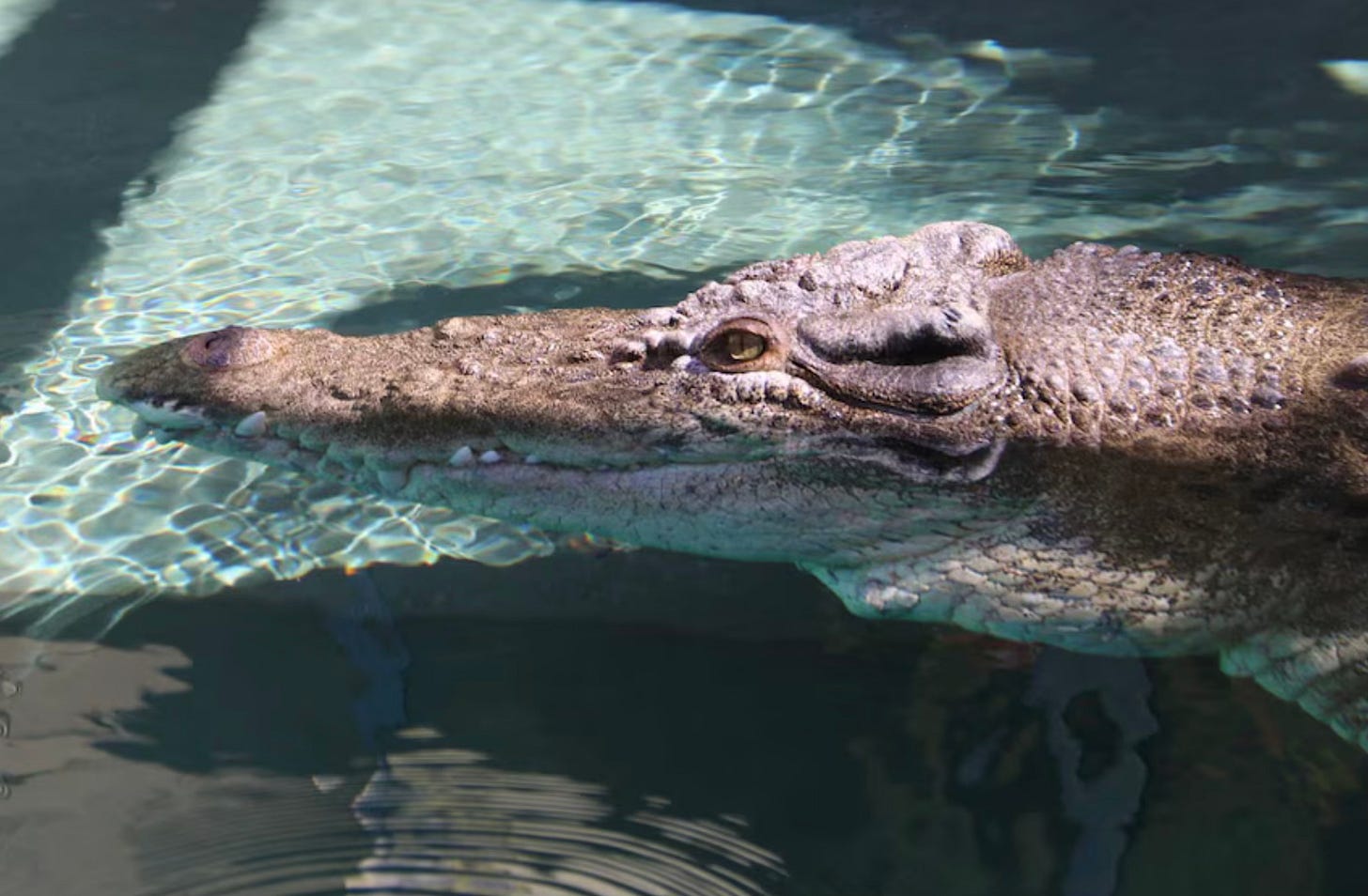

I started this essay a year ago, but have only just got round to finishing it. I was spurred on by a promise I made to one Substack reader that I would write about crocodiles next. I am but am doing most of this writing privately, patiently, submerged in a river of my own muddy thoughts and meanderings, with the knowledge that I can’t imagine anyone else wanting to read about my crocodile obsession, given I have never been attacked by a crocodile or worked with them in any real capacity. But that does not mean I haven’t thought about crocodiles deeply…

_

Burt has died several days shy of Christmas. This no longer matters to him because he is dead, and also because he doesn’t know what Christmas is. In the Guardian Obituary he was described as a force of nature, with a great personality. He was one of a kind the article said. Untrue. Burt was one of many saltwater crocodiles, he was an exemplar of his species. I also discovered from reading his obituary that several casts of Burt were made for use in the film Crocodile Dundee.

Ha! I had no idea that the crocodile in the film was based on a real-life specimen, a specific saltie. Now, I am trying to absorb the ‘Burtness’ of the crocodile that snatches the big pendulous enticing water bottle from around Linda Kozlowski’s neck in the movie. I am relating not just to the terror of the saltwater crocodile, but to Burt.

A dim memory in the Odeon cinema. The suspense—the crowd seated in those red fabric flip-up seats (not unlike the scissoring jaws of a crocodile, each seat had the ability to snap closed abruptly) as we watched the scene unfold, I sat tensely in my red velveteen seat, my hands covering my eyes, stealing quick glimpses through my fingers at the water on screen, dense, and impenetrable, the folly of Linda Kozlowski’s character was obvious to everyone in the cinema. We were held in the dark like hatchlings watching and waiting.

Linda sets off to prove that even though she’s a Shelia she can handle the outback alone (she can’t). She wears a gauzy little mosquito net draped around her shoulders, and removes it, stretching slowly and sensuously by the lily-clad billabong. The on-screen soundtrack suddenly drops the thrum of insects and launches into a romantic orchestral serenade. Mick J Crocodile Dundee hits his head on an overhanging tree as he watches her shed her sarong and move toward the water to refill her water bottle. Her tanned buttocks are magnificent. Even now I feel a kind of awe, somehow the bareness of her behind, its very brazenness, is matched by the crocodile that suddenly launches from the water. Burt!

Linda screamed (I think). The burst of Burt’s head sent my heart pounding too; I almost leapt from my seat as though I was being attacked. The crocodile’s eyes demonic, as it clutched not her head but the water bottle hanging around her neck. She grunted, her hands clasped the leather straps, and they entered a tug of war. (Quite handy, as if Burt had gripped her head she might have been decapitated, which happened to a fisherman in a real-life attack at Cahill’s Crossing.) The on-screen trigger had finally been released, and the orgy of waiting was over. The audience could now deal with the consequences of being caught.

Mick J Dundee has thankfully been watching Linda bathe from a nearby perch on a tree, and swings into action. He stabs the crocodile rolling around with it, instead of Linda, in a heroic ballet of guts and blokey know-how. He drives the knife into the croc, twists and twists. He stabs poor Burt in the back.

Then he hugs Linda who clings to him, almost as tightly as the crocodile had clung to her water bottle strap. In case you are one of the rare people who do not have an image of Mick J Dundee already in your head...he is the forty-six year old actor Paul Hogan. Linda is fretful, quivering, cowering inside his shoulder, she cleaves to him. “It’s over now,” he says.

“Is it dead?” she asks.

“Well, if it isn’t, I’m going to have a hell of a job skinning the bastard,” he replies.

The camera then cuts to a full body shot of Burt— large, green, ghoulish, that crocodilian mouth closed in a rigor mortis grin. Burt at this point in the narrative looks slightly sheepish. I assume he was sedated for the moulding process? How does one make a cast of a large crocodile?

Burt’s role in Crocodile Dundee was small, but he was over sixteen metres long. I learned he had died at Crocosaurus Cove in Darwin, where he had lived since the early eighties after being removed as a “problem croc” from the Reynolds River. Burt was named after the actor Burt Reynolds! Burt (the croc) later starred in Rogue, another movie I have seen. There are few crocodile films I have not watched though Crocodile Dundee must have been the first.

A representative from Crocosaurus Cove said, “While his personality could be challenging, it was also what made him so memorable and beloved by those who worked with him and the thousands who visited him over the years.”

I respect Burt as I too have a challenging personality. I thought of calling Crocosaurus Cove and asking for more information on his personality. But then...what? I dare not actually go to Crocosaurus Cove and pay to enter the see-through cylindrical “cage of death”, to be lowered into the water and spend 15 minutes in the proximity of the personality of one of the large saltwater crocodiles currently listed on the website: Wendell, Baru, Leo, or William and Kate.

Instead, I did the sensible thing and rewatched Crocodile Dundee.

It is hard to overstate the influence of Crocodile Dundee. Released in 1986, I saw it at my local cinema when I was twelve years old, think I was with Mum? Not sure if I still wanted a palaeontologist at that age. Maybe not. I would have consumed the film in the spirit it was intended, with a big cup of coke and a bowl of tangy fruits. The film was a giant global hit that drove American tourists to Australia, and I can see why, though I personally don’t think the scene with Burt would have encouraged me to book a flight.

I rewatched it recently, and against my better judgment, I still felt in succour to Paul Hogan’s portrayal of Mick Dundee. In one telling and iconic scene he brings down a water buffalo by holding two fingers out in a position so that they echo the water buffalos’ horns and hums a faintly digerdoo-ish tune. The buffalo lies down and keels over, in the dirt. It’s not a swoon, but that moment stands in for the entire film. Before Mick Dundee, animals and women kneel.

He is in touch with the landscape—like the aborigines who raised him—and he is also in touch with Linda Kozlowski who plays a journalist from New York called Sue. A writer! I had completely forgotten this subplot. The role of writer can really help a woman get around. Sue is the native New Yorker, who heads to Walkabout Creek to hunt down the story of a man attacked by a crocodile (Mick!), that allegedly tore off his leg (untrue) who then survived alone for weeks, before crawling out of the outback. She also looks good enough to eat in a black G-string from the back.

The scenery is magnificent; in the rushes they glide through the beauty of the river, passing trees that rise out of the water, and various lilypads. This is Eden, with teeth. I did enjoy their long expedition through Kakadu Park, to the dried-up river where his aluminium boat is wedged in the crook of a tree.

He rolls up his trouser leg and shows her where he was attacked. “More of a love bite really.” Then describes the death roll, slowly, menacingly.

“The death roll?” Linda, in character as the writer, enquires. Everything is fodder for her story. She asks if he was hunting crocodiles. Mick replies, “Nah, that’s illegal. I was fishing.” She picks up a handful of bullet shells from the bottom of his boat. “Just fishing?”

“Barramundis are big bloody fish,” he says.

Mick is a hardcase, and thick skinned like a saltie. Crocodiles were hunted to near extinction in Australia, until 1971 when hunting was banned, and the crocodile population began to recover. The implication that Mick is hunting and shooting crocs is thinly disguised. So long Burt, and good riddance, the resilience of crocodiles as a species is never held in question.

The story follows Dundee and Linda back to New York for a croc out of water story. Dundee’s salt of the earth character is pitted against the sophistication and folly of New York’s urban jungle. When attacked by an extra with a switch blade wearing a red leather “Beat it” style jacket, Mick withdraws his shiny croc knife from his sheath, “That’s not a knife, this is a knife.” Presumably it is the same instrument that stabbed Burt in the back. At twelve, this scene was hilarious, and Mick was a hero. At fifty-one, my attitude hasn’t changed as much as it should.

I should unsheathe my critical blade, and slay the patriarchal myth of Crocodile Dundee, but I don’t have the heart for it. Yes, it perpetuates terrible stereotypes of toxic masculinity and the noble savage. Mick is aligned with the aboriginal characters, especially Neville Bell, played by actor David Gulpilil who is in on several “primitivist” jokes, but there is no further specificity to the portrayal of Country. The movie was filmed in Kakadu Park; the traditional owners are Bininj in the north and Mungguy in the south. Despite the importance of the crocodile to the plot and to Mick’s character, there is no acknowledgement of the crocodile’s status as an ancestor and totem in Dreamtime stories.

Yet I still find Mick J Dundee’s glass at least half full of Fosters. By the time Crocodile Dundee was filmed, Hogan was already a well-known comedian in Oz, nicknamed “the Hoges”, who’d had his own TV show and starred in several successful ads for the Australian Tourism Commission. One ad featured a classic line about throwing another shrimp on the Barbie. In another advert set in the London underground a tourist asks Hogan how to get to Cockfosters. “Yeah, drink it warm mate,” Hogan replies, holding up a beer can. Hogan co-wrote Crocodile Dundee and Mick was his comic invention. No wonder he wore that croc skin waistcoat so well.

I rewatched the Lilypad crocodile attack several times. My reptilian brain still pricked with fear. I had to lean back from my screen. When Burt bursts through the waterlilies I can tell he’s a prop, but he’s a blood good one, mate!

As a little girl, the crocodile attack was the money shot and I would have felt cheated without it. I moot Burt’s challenging personality still maketh the movie. I remember being terribly disappointed by Crocodile Dundee II because it had no crocodile scene. The only comparative moment was when Mick was dressed in a skinned croc head suit and pretended to catch his mate Wally the tour guide and drag him under the water. Not good enough! If a film has crocodile in the title, I want to see a live crocodile in it, and it better be a man eater.

Hogan later filmed Crocodile Dundee III set in LA. Have not seen it. The other day I spent about fifteen minutes watching The Very Excellent Mr Dundee on Amazon Prime and was surprised to see John Cleese in one scene. Hogan plays himself trapped as a “one hit wonder” forever listening to botched versions of his own one-liners. No crocodiles. Next, I wanted to watch Love of an Icon, a documentary on the making of Crocodile Dundee. The trailer includes a snatch of an animatronic Burt in the waterlilies. “It’s $7.99 to rent,” I told my partner. He said nothing. “One for me to watch alone, perhaps?” “I think so,” he replied.

I still find comfort in Paul Hogan as Mick Dundee. I cleave to the cliches. After the croc attack, he cuddles Linda, “I’ve got you,” he says, wiping her hair from her face. I find the moment surprisingly tender, almost paternal. Linda is twenty years his junior. Their age gap is about the same as my father and me. I can see the sweat on her and him, the anguish in her eyes. Don’t we all secretly long for a capable father, who will protect us from the jaws of the crocodile and love us unconditionally?

Hogan fell in love with Linda on the set of Crocodile Dundee and left his first wife Noelene. I later read a Woman’s Weekly article about Noelene. I looked at her homely photographs, she was blonde and middle aged, they had five kids together. Noelene was no candidate for the black G-string scene, though I don’t think Burt would have discriminated against her. I pitied Noelene, took her for the victim in the story. Even though the article also contained commentary from a female clairvoyant who suggested that Paul, Noelene and Linda were locked in a cycle of karmic retribution to do with their past lives. I’m not sure of the details now, I’m not even sure the article was in a Woman’s Weekly magazine. Woman’s Day, maybe?

But I do know that sometimes I still find being a woman hard to swallow.

Yes Being Prey is the best crocodile essay I've ever read. I have been working across a range of material and that is part of my evolution. the attack on Val was about a year before they filmed Crocodile Dundee in Kakadu. It's a fantastic piece of writing and her take on being prey is life changing....really.

Firstly, I want to say that I'm the exact age Paul Hogan was in that movie & that makes me feel better about myself. (NZ sun is bad but Australian sun is worse...)

Secondly, if you haven't read it already (I assume you have if you're a crocodile nerd) I recommend Val Plumwood's account of being attacked by a crocodile while kayaking in Kakadu National Park. It's called 'Being Prey' & I found out about it from Stephen Harrod Buhner's excellent eschatology-tinged book 'Earth Grief': basically he argues that our human hubris leads us to think of ourselves as always the eater, never the eaten, which is unnatural.